Revisiting the 2008 GFC

An examination of how collective biases changed our world forever...

Leading up to the collapse

During the turn of the millennium, from the late 1990s through the early 2000s, both the United States and the broader global economy enjoyed periods of robust growth and stability. This economic boom was partially fueled by significant deregulation efforts within the financial sector. Notably, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 effectively dismantled key provisions of the Glass-Steagall Act, thereby removing the barriers that had historically separated commercial and investment banking activities.

In reaction to the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2001 coupled with the economic implications of the September 11 attacks, the Federal Reserve implemented policies that maintained low federal interest rates to foster an environment conducive to borrowing and investing. The availability of low-cost borrowing encouraged financial institutions to extend more loan offerings, which included extending credit to individuals with poor credit histories.

The era was also marked by significant financial innovation, particularly with the advent and increase in complexity of financial instruments such as mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). These instruments mixed high-risk mortgages with other types of debt, which camouflaged the inherent risks and made them highly appealing to investors like pension funds and corporate treasuries. This allure was predicated on the perceived security and attractive returns of these financial products.

What is a CDO?

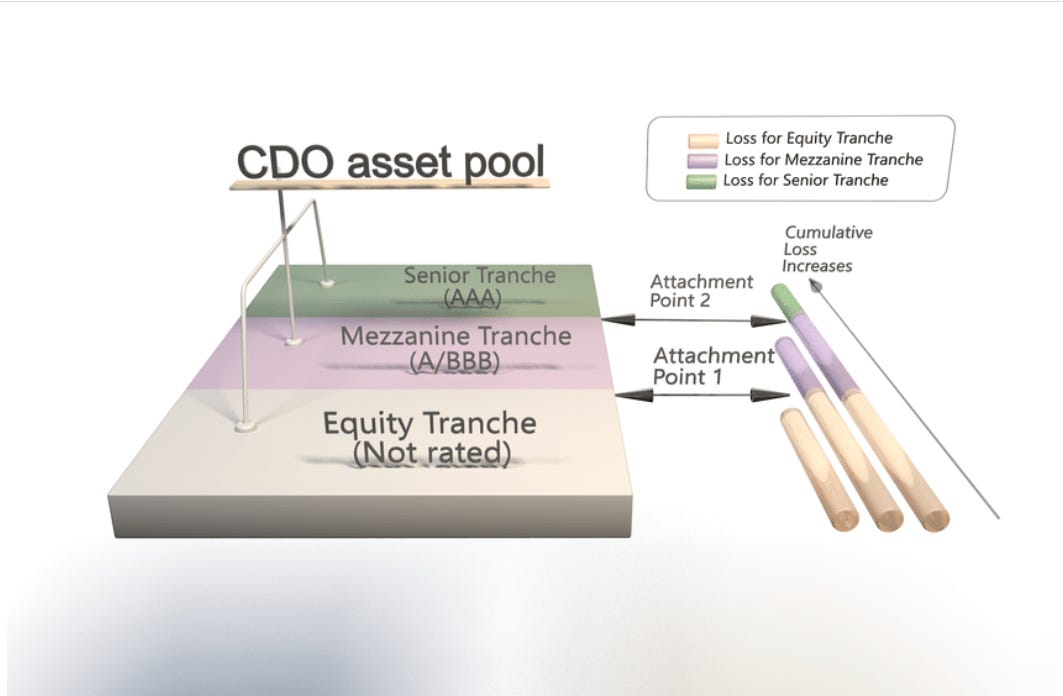

Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) were pivotal in escalating the risk from subprime mortgages leading up to the 2008 Financial Crisis. These complex financial instruments combined various debts like mortgages, bonds, and loans into single products sold to investors, featuring multiple risk layers:

Complexity and Misunderstood Risks: CDOs had different risk levels across tranches; senior tranches appeared safe, protected against defaults, while junior tranches took initial losses. Yet, the real risk was often masked by the securities' intricate structures and their interlinked debts.

High Leverage Practices: Financial institutions leveraged heavily with CDOs, holding minimal capital against potential losses. A minor decline in asset values could trigger substantial losses, exacerbated by the assumption that asset prices, especially house prices, would continually rise.

Flawed Credit Ratings: Agencies like Moody's, S&P, and Fitch often assigned optimistic ratings to CDOs based on defective assumptions about the mortgage market and economic conditions. These ratings were also compromised by the issuer-pays model, which posed a conflict of interest.

Impact of Subprime Defaults: The riskiest, lower tranches of CDOs, mostly backed by subprime mortgages, suffered enormous losses as homeowners defaulted due to economic strain or rising interest rates, spreading distress to even the upper, supposedly secure tranches.

In essence, CDOs magnified the financial system's vulnerability through complexity, leverage, and flawed ratings, culminating in widespread losses once the housing bubble burst.

The Bubble and Subsequent Burst

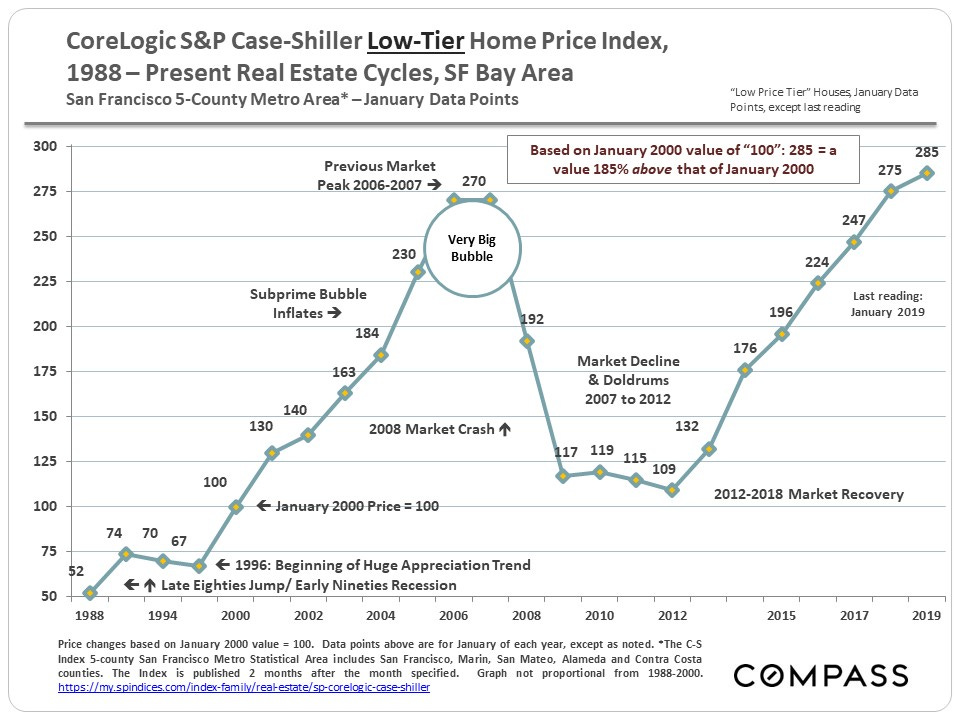

In the early 21st century, there was a notable surge in the cost of homes, driven by a combination of low interest rates, liberal credit conditions, and a boom in real estate speculation. The notion of owning a home became a central element of the American dream, leading to an increase in subprime mortgages, which are loans targeted at individuals with a spotty credit history.

Financial institutions, including banks and mortgage lenders, extended these subprime loans to individuals deemed high-risk because they might not have the capacity to repay. These risky debts were then bundled into Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS) and sold off to investors, thus dispersing the potential risk of borrowers defaulting across the broader financial network.

A significant portion of these subprime loans were structured as adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs). These ARMs initially charged low-interest rates that were set to increase significantly after a predetermined period. As a result, when the introductory low rates expired and were adjusted upwards, many homeowners found themselves unable to afford the new, steeper payments, leading to a high rate of defaults on these mortgages.

The pivotal shift occurred in 2006 as housing prices plummeted while interest rates climbed. This combination proved disastrous for subprime borrowers, triggering a spike in loan defaults. As defaults increased, the market value of Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) and Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) plummeted, resulting in significant financial losses for numerous institutions.

In March 2008, the unraveling of significant financial entities commenced with the downfall of Bear Stearns, which was hastily acquired by JPMorgan Chase in a deal orchestrated by the Federal Reserve. The turmoil intensified with Lehman Brothers' bankruptcy on September 15, 2008, marking the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history at that time. This bankruptcy profoundly disturbed the financial markets and led to a worldwide retreat from lending practices.

A subsequent pivotal episode was the government bailout of AIG, a key insurance giant, which had underwritten numerous MBS and CDOs. AIG's failure to absorb the default losses necessitated federal intervention to avert a total financial meltdown, highlighting the depth of the crisis.

Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases significantly influenced the judgment of investors, credit rating agencies, financial entities, and regulatory institutions prior to and during the economic meltdown. The primary cognitive biases that affected their decisions included:

Overconfidence Bias

Numerous financial actors, including bankers, traders, and regulators, placed undue faith in their risk assessment methodologies. A prominent example is the Gaussian copula function, which was employed to predict the interplay between different securities. This misplaced trust in mathematical models played a role in the gross underestimation of both the probability and potential severity of the looming crisis.

Confirmation Bias

There was a strong tendency among investors and financial experts to embrace information that supported their preconceived notions of perpetual market expansion while disregarding conflicting indicators. The extended phase of economic stability known as the "Great Moderation" caused many to ignore the accumulating risks posed by heightened leverage within the financial system.

Myopia (Short-termism)

Short-term objectives heavily swayed many financial decisions. The prevalent focus on immediate metrics such as quarterly performance, yearly rewards, and short-term market gains detracted from the considerations necessary for long-term investment stability, thus promoting hazardous and aggressive financial maneuvers.

Herd Behavior

A notable herd instinct was observed as both investors and financial institutions replicated the investment strategies of their counterparts. The initial success and subsequent popularity of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) led many to follow suit, contributing to a collective movement that often bypassed meticulous, independent analysis.

Anchoring Bias

Investors often depended excessively on historical data regarding housing prices to back continuous investments in the real estate sector and its associated securities. This anchoring to past price trends fostered expectations that property values would forever ascend, causing many to disregard signs of an impending housing bubble.

Illusion of Control

Those at the helm of creating complex financial instruments, such as various configurations of CDOs, MBS, and credit default swaps (CDS), believed they could manage these convoluted systems effectively. This overestimation of their control over financial instruments significantly contributed to the culture of excessive risk-taking.

Takeaways

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis serves as a profound tutorial on the interactions among market behaviors, regulatory frameworks, and human psychological tendencies, which collectively led to widespread financial disruption. Central insights from the debacle highlight the importance of strict regulatory supervision to effectively handle sophisticated financial instruments such as Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs). These instruments' inherent risks were compounded by their complexity and the conflicting interests within credit rating agencies. The crisis spotlighted the perils tied to high leverage ratios and underscored the critical need for transparency to ensure market stability. To navigate beyond inherent biases, it is crucial to develop an understanding of common cognitive errors, like overconfidence and confirmation bias, acknowledging the imperfections in human judgment prone to collective misdirection. Financial entities need to adopt comprehensive risk evaluation frameworks that prepare for extreme conditions, whereas investors must focus on sustainability over immediate profits. Drawing lessons from this crisis involves imposing tougher capital regulations, enhancing underwriting standards' quality, and promoting a culture that values skepticism and independent checks in financial practices. These measures are essential to building a sturdier financial infrastructure capable of coping with the intricacies of worldwide economic dependencies.

Links:

Stages of the 2007/2008 Global Financial Crisis: Is There a Wandering Asset-Price Bubble?

Summary:

This research delineates five critical phases of the ongoing global financial crisis: firstly, the collapse of the subprime mortgage sector; secondly, its repercussions on the wider credit markets; thirdly, the liquidity crunch exemplified by the collapse of major financial entities like Northern Rock, Bear Stearns, and Lehman Brothers, which exacerbated counterparty risks across the financial spectrum; fourthly, the surge and burst of the commodity price bubble; and finally, the downfall of the U.S. investment banking sector. The intensity of the crisis, according to the study, is predominantly driven by the volatile distribution of global savings and rampant credit expansion, resulting in asset overvaluation across various categories. The research terms this phenomenon a "wandering asset-price bubble", where the erratic distributions amplify market, credit, and liquidity risks. It suggests monetary policies aimed at financial stabilization in response to these challenges.

The Role of Cognitive Biases in the Fluctuation of Traditional and Modern Financial Markets

Summary:

The article "The Role of Cognitive Biases in the Fluctuation of Traditional and Modern Financial Markets" examines the influence of cognitive biases on both traditional (stocks, bonds) and modern (cryptocurrencies) financial markets. It defines cognitive biases as irrational judgment patterns that can lead to market inefficiencies. Key biases discussed include overconfidence, which causes investors to underestimate risks; confirmation bias, which skews information processing to affirm preconceived beliefs; and herd behavior, which can lead to asset bubbles and crashes.

In traditional markets, these biases have historically contributed to significant financial disruptions, exemplified by the 2008 financial crisis where herd behavior amplified market volatility. Modern financial markets, characterized by their high volatility and less regulation, see these biases manifest more sharply, with the rapid pace and emotional trading exacerbating the effects and leading to pronounced market swings and speculative bubbles.

The article advocates for strategies to mitigate these biases to stabilize financial markets, emphasizing the need for improved financial education, stronger regulatory frameworks, and advanced technological tools for better investment decision-making. Both market types, while affected by similar biases, exhibit different susceptibilities and impacts, highlighting the necessity for tailored approaches to address these cognitive distortions in the financial landscape.