Macro Update: Navigating Conflict, Constraints, and Capital Markets

June's Macro update

The last couple of months have served up no shortage of market-moving developments… geopolitical flare-ups, tariff tremors, and the ever-slowing drip of economic data. Through it all, the U.S. economy remains remarkably resilient, even as old fears of a recession linger beneath the surface.

Let’s begin with the most immediate wildcard…

The Israel-Iran conflict

This past weekend marked a dangerous escalation, with Israel launching strikes on Iranian sites, and the U.S. (under Trump’s watch) effectively greenlighting the move. Military analysts can debate strategy, but for investors, the first-order concern is oil. A wider war, or a disruption to the Strait of Hormuz, would send energy prices higher and shake global markets. But you already knew that. The real question is what this means for policy, inflation, and the Fed.

Trump, famously averse to starting foreign wars, campaigned on keeping U.S. troops out of new conflicts. That promise still matters. I suspect his base has little appetite for another Middle East quagmire, and unless all options are exhausted, direct U.S. engagement remains unlikely.

More probable?

A calculated use of pressure to force Iran into negotiations, potentially setting the stage for a nuclear peace deal. A flashy handshake photo-op might suit Trump’s playbook far more than boots on the ground.

But here's where it gets interesting: the ripple effects on Trump’s broader agenda.

Oil price spikes create a chain reaction; higher inflation, higher bond yields, and a hawkish Fed. All of these are counterproductive to Trump's priorities: cutting rates, refinancing debt at lower costs, and avoiding a recession heading into an election year.

So, even as he navigates global flashpoints, Trump is constrained by the domestic consequences they trigger.

That brings us to the framework we’ve consistently emphasized: restrictions over predispositions.

When evaluating policy outcomes, especially on trade, rates, or foreign affairs, it’s less useful to ask, “What does Trump want?” and more helpful to ask, “What is he boxed in by?”

Previously, we highlighted three core limiting factors:

Debt financing (i.e., 10-year Treasury yields)

Tax bill passage and fiscal headroom

Recession risk in an election cycle

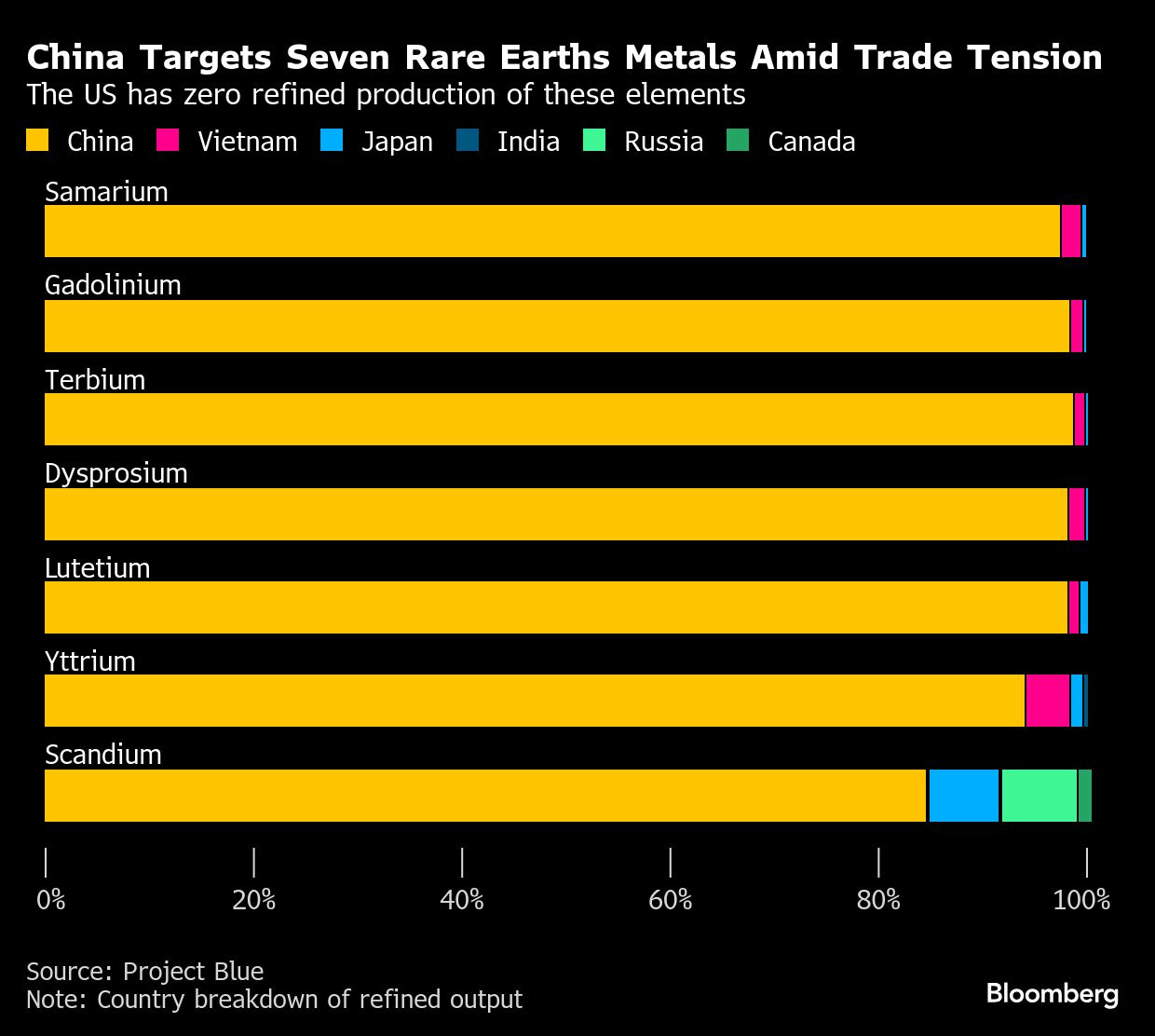

Rare earth mineral dependence, particularly in the context of U.S.-China trade dynamics, is also becoming a strategic bottleneck and could shape how aggressive the U.S. can afford to be on tariffs and tech restrictions.

Speaking of trade… remember tariffs?

The specter of tariff-induced inflation has returned, but we continue to view it as transitory. Goods inflation may tick higher due to tariffs, but this is likely to be offset by cooling services inflation, especially in shelter and rent. As we’ve noted before, rent tracks wage growth, and wage growth is already slowing in line with a softening labor market.

If not for the lingering uncertainty around tariff policy, and its implications for inflation optics, the current macro setup might already justify Fed rate cuts. The economy is cooling but not collapsing. Services inflation is easing. The labor market remains intact, but wage pressure is fading. On balance, the conditions are there.

Ultimately, this all ties back to Trump’s finite political capital. Each new shock, whether a regional war, inflation flare-up, or trade tiff, drains his ability to push other priorities forward.

The calculus then becomes: what does he concede in one area to stay viable in another?

If escalation in the Middle East forces his hand on energy prices and yields, expect some dialed-down rhetoric, or outright concessions elsewhere. Trade policy is a likely candidate. And that’s where we, as investors, should be watching closely.

The US-China Trade Dance: From Reconciliation to Realism

In our last macro memo, we laid out a framework for understanding the U.S.-China relationship, one rooted not just in ideology or posturing, but in mutual constraints and tactical incentives. That thesis has largely held up.

Shortly after that memo went out, the U.S. and China entered trade talks in Geneva. The results were surprisingly constructive. Both sides agreed to pause their tit-for-tat tariff war, and Presidents Trump and Xi followed with a direct phone call. Mutual state visit invitations were exchanged, and Trump declared a deal was “already reached”, only minor details remained to be finalized.

For a brief moment, it looked like the U.S. and China had gone from Cold War to cuddle session.

But reality set back in quickly.

The next round of talks, held in London, was framed as a formality to iron out remaining issues. Instead, they dragged on with little resolution. The end result was a vague “positive framework.” It became increasingly clear that even if Trump himself isn’t ideologically committed to economic decoupling, he’s operating within a U.S. political environment that absolutely is. There’s now bipartisan consensus that strategic disentanglement from China is not just preferable, but necessary.

This is no longer a fight over tariffs. It’s the beginning of a slow-motion negotiated divorce, and neither side can afford to walk away entirely. The U.S. holds critical advantages in advanced semiconductors, aircraft parts, and global consumer demand. China, meanwhile, dominates the rare earth minerals supply chain, particularly refinery capacity, a vital input for U.S. defense and industrial production. Both sides are using their leverage as bargaining chips. Neither has a clean exit…

From an investor’s standpoint, this means that tariffs and trade tensions aren’t going away, they’ll ebb and flow, driven by each side’s domestic political and economic pressure points.

For President Xi, the pressure is economic. Despite a recent narrative shift driven by China’s push into AI and robotics, the underlying fundamentals remain fragile. China’s property bubble continues to deflate, youth unemployment is alarmingly high, and core deflation lingers.

Consider this perspective:

While the U.S. enjoys a genuine economic surge despite negative sentiment, China is trapped in a superficially positive mood amid an actual economic downturn.

Since early 2024, Beijing has responded with sizable fiscal stimulus. At the National People’s Congress, China set ambitious growth targets and gave local governments latitude to issue long-term debt. That was followed by real estate lending support and consumption incentives. These measures have helped improve sentiment, and stocks, as always, bottom before fundamentals.

But the deeper takeaway here is why China wants a deal. A weak economy erodes legitimacy, even in autocratic regimes. Xi needs a win, and stable trade relations with the U.S. would help ease both external pressure and internal unrest.

On the U.S. side, Trump is facing his own complex calculus. In addition to the economic constraints we outlined previously (inflation, bond yields, recession risk, and tax legislation), we now add rare earth minerals as another limiting factor. It’s not easy to take a hard line when your defense supply chain depends on your rival’s exports.

More importantly, Trump has a personal preference for striking a “big deal” with China. He sees it as a legacy-defining win, a demonstration of his self-styled negotiating prowess. And there’s public opinion to consider.

Tariffs aren’t popular.

The bottom line? While full decoupling is off the table, a stable, strategically constrained trade relationship is not only possible… it’s likely.

Both leaders want a deal, albeit for very different reasons. And as long as neither economy tips too far into distress, we remain constructive on the path forward for U.S.-China trade.

Labor Market Slows, But the Fed Stalls… For Now

Outside of trade war tremors, the U.S. economy continues to hum along, not booming, but not breaking either. One of the clearest indicators of this economic resilience lies in the labor market, which has entered a kind of uneasy equilibrium.

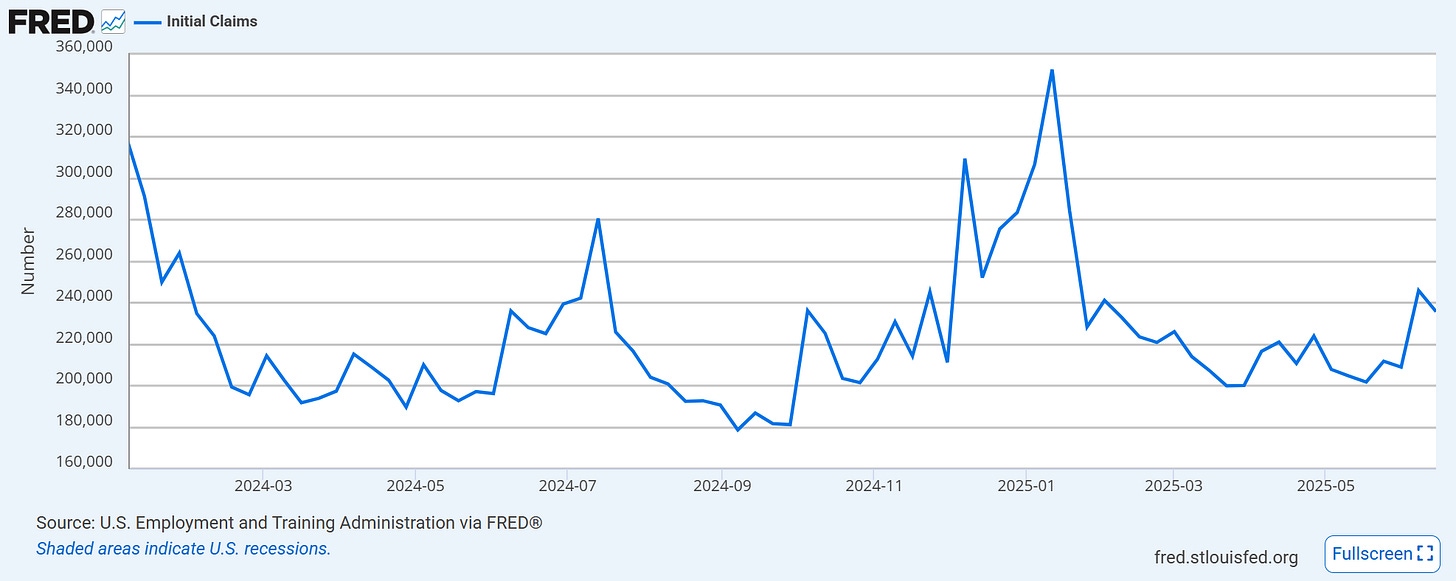

Job growth remains positive, but the underlying dynamics are shifting. Initial jobless claims have held steady, while continuing claims, which track those who remain unemployed, are quietly climbing to multi-year highs.

Translation?

People who lose jobs aren’t finding new ones quickly. At the same time, nobody’s quitting, and companies aren’t doing much hiring either. Attrition is down, and the post-COVID overhiring spree has left employers cautious. As a result, many job seekers are now facing long spells of unemployment, often without so much as an interview.

This stalling labor churn is showing up across metrics. Job openings are trending downward. The unemployment rate, which bottomed in 2023, is now drifting higher.

Some argue that recent reductions in illegal immigration might constrain labor supply and keep unemployment low. I’m pretty skeptical of this. High immigration didn’t prevent unemployment from falling in prior years, and reversing that doesn’t seem likely to change the macro labor picture significantly now.

All told, we expect the unemployment rate to continue creeping higher… slowly but surely.

Which brings us to the Fed.

Earlier this year I made the case that the Fed could resume cutting rates by June. That turned out to be a bit early, but I stand by the logic.

Inflation, by most measures, has been tamed, and barring new shocks, there’s little justification for policy rates to remain this high.

The Fed’s own framework for cutting last year (lower inflation = lower rates) still applies.

So why hasn’t the cutting cycle resumed?

In a word: tariffs.

Trump’s aggressive trade policy is injecting new uncertainty into the inflation outlook. The Fed doesn’t want to repeat the mistakes of the early 2020s… or worse, the ghost of Arthur Burns in the 1970s.

Ironically, the same Trump who wants lower rates is creating the very inflation optics that make Powell hesitant to cut. It’s a strange dynamic to say the least…

These concerns are somewhat misguided.

The inflationary effects of tariffs are likely to be mechanical and temporary, not sticky or systemic. Trump’s tariffs mostly apply to goods, not services, and the U.S. is a service-heavy, largely closed economy with limited exposure to imported goods. Even if we do see some goods inflation, it will likely be offset by continued services disinflation, especially in rent and shelter, which are driven by wage growth. And wage growth is already softening.

The call: (You heard it here first)

I expect Powell to open the window to rate cuts at the July FOMC. The updated dot plot may start showing a few members shifting their projections lower for year-end, even if the median dot stays unchanged for now. Once that signal is out there, markets will likely start pricing in an autumn cutting cycle.

Positioning for the Next Rotation: Dollar, Commodities, and Selective U.S. Strength